UNTP Purpose

The United Nations Transparency Protocol (UNTP) aims to support governments and industry with practical measures to counter greenwashing by implementing supply chain traceability and transparency at the scale needed to achieve meaningful impacts on global sustainability outcomes.

- Short UNTP Presentation PDF PPT

- Longer UNTP Presentation PDF PPT

- Video presentation (15 mins) Youtube

Incentives for sustainable supply chains are increasing fast.

- Regulations such as the European Regulation on Deforestation (EUDR) and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will present market access barriers or increased border tariffs for non-sustainable produce.

- These regulations impose due diligence obligations on entire supply chains, not just final products. Penalties for repeated non-compliance can be as high as 4% of global revenue.

- Financial institutions are rapidly moving to ensure that capital is preferentially focussed on ESG assets. According to Bloomberg, within a few years, around $50 Trillion or one third of all global assets under management will be ESG assets.

- Consumer sentiment is driving purchasing decisions to favour sustainable products. At the same time, consumers are increasingly mistrustful of unverifiable claims and look for third party certification based on trusted standards.

Greenwashing is a term used to describe a false, misleading, or untrue action or set of claims made by an organization about the positive impact that a company, product or service has on the environment or on social welfare. Just as the incentives described above provide a strong motivation for genuine sustainability in products, so they also provide stronger motivations for greenwashing.

The evidence from multiple research activities is that greenwashing is already endemic with around 60% of claims being proven to be false or misleading. This presents a significant threat to sustainability outcomes. But there is room for optimism because around 70% of consumers expect higher integrity behaviour and are willing to pay for it. There are two plausible pathways ahead of us.

To win the race to the top, fake claims need to be hard to make. The best way to achieve that is to make supply chains traceable and transparent so that unsustainable practices have nowhere to hide. But, to have any impact, the traceability and transparency measures must be implemented at scale.

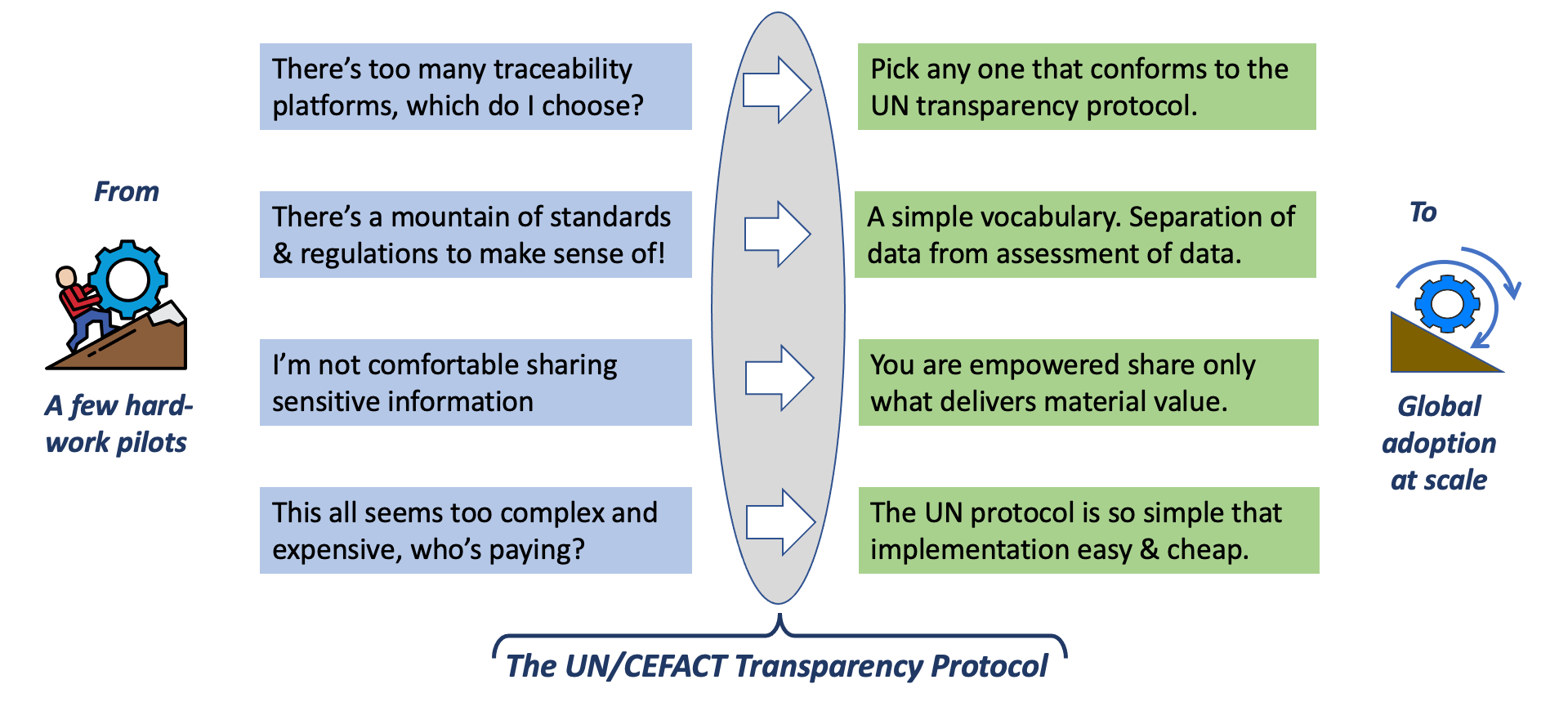

The world's supply chains must reach to the point where digital verifiable traceability and transparency information are available to meet regulatory compliance, satisfy investors, and motivate consumers for the majority of products on the market. However, achieving transparency at that scale presents some challenges.

- Which software to choose? There are many traceability & transparency solutions on the marketplace. Many expect all actors in a given value chain to subscribe to the same platform in order to collect the data for end-to-end traceability. However, just as expecting your customers and suppliers to create accounts at your bank so that you can pay them is not rational or practical (that's why inter-bank payment standards exist), so the adoption of all actors in value chains to one platform is also not feasible or scalable. The UNTP is a standard protocol, not a platform, and assumes that supply chain data remains with each natural owner. So the answer to "which software to choose?" is "pick any, so long as it conforms to the UNTP".

- Coping with a growing mountain of ESG standards and regulations. The current count of ESG standards and regulations around the world runs into the thousands. Some are specific to particular commodities, jurisdictions, or ESG criteria and some cover multiple dimensions. There is very significant overlap between them and very little formal mutual recognition. The consequence is that it becomes very challenging for supply chain actors that sell to multiple export markets to know which criteria matter and how to demonstrate compliance. There is a risk that too much of the available ESG incentive is spent on demonstrating compliance and too little is left for implementing more sustainable practices. The UNTP does not add to the complexity by defining more ESG standards. Rather it seeks to minimise cost of compliance by making it simpler to test on-site ESG processes and data against multiple ESG criteria. Essentially this is about implementing a sustainable practice once and then re-using it to satisfy multiple overlapping criteria.

- Protecting confidential information. "Sunlight is the best auditor" and so verifiable transparency is the best greenwashing counter-measure. However, increased supply chain transparency for ESG purposes also risks exposure of commercially sensitive information. A viable transparency protocol must allow supply chain actors to share ESG evidence whilst protecting sensitive information. Rather than dictate what must be shared and what should not, the UNTP includes a suite of confidentiality measures that allow every supply chain actor to choose their own balance between confidentiality and transparency. The basic principle is that actors should be empowered to share only what delivers value.

- Making a business case for implementation. Each supply chain actor (or their software provider) will need to make a viable business case for implementation of the UNTP. The transparency incentives discussed in this section represent the benefit side of the equation. To keep the cost side as low as practical, UNTP has a strong "keep it simple" focus and offers a suite of implementation tools to further reduce cost. Some sample business case templates are provided to help actors make their case for action.

The UNTP provides a solution to the transparency challenges facing the world's supply chains. By implementing a simple protcool that can be supported by existing business systems, stakeholders will realise immediate benefits and will become visible contributors to the sustainability of global supply chains.

UNTP Architecture Overview

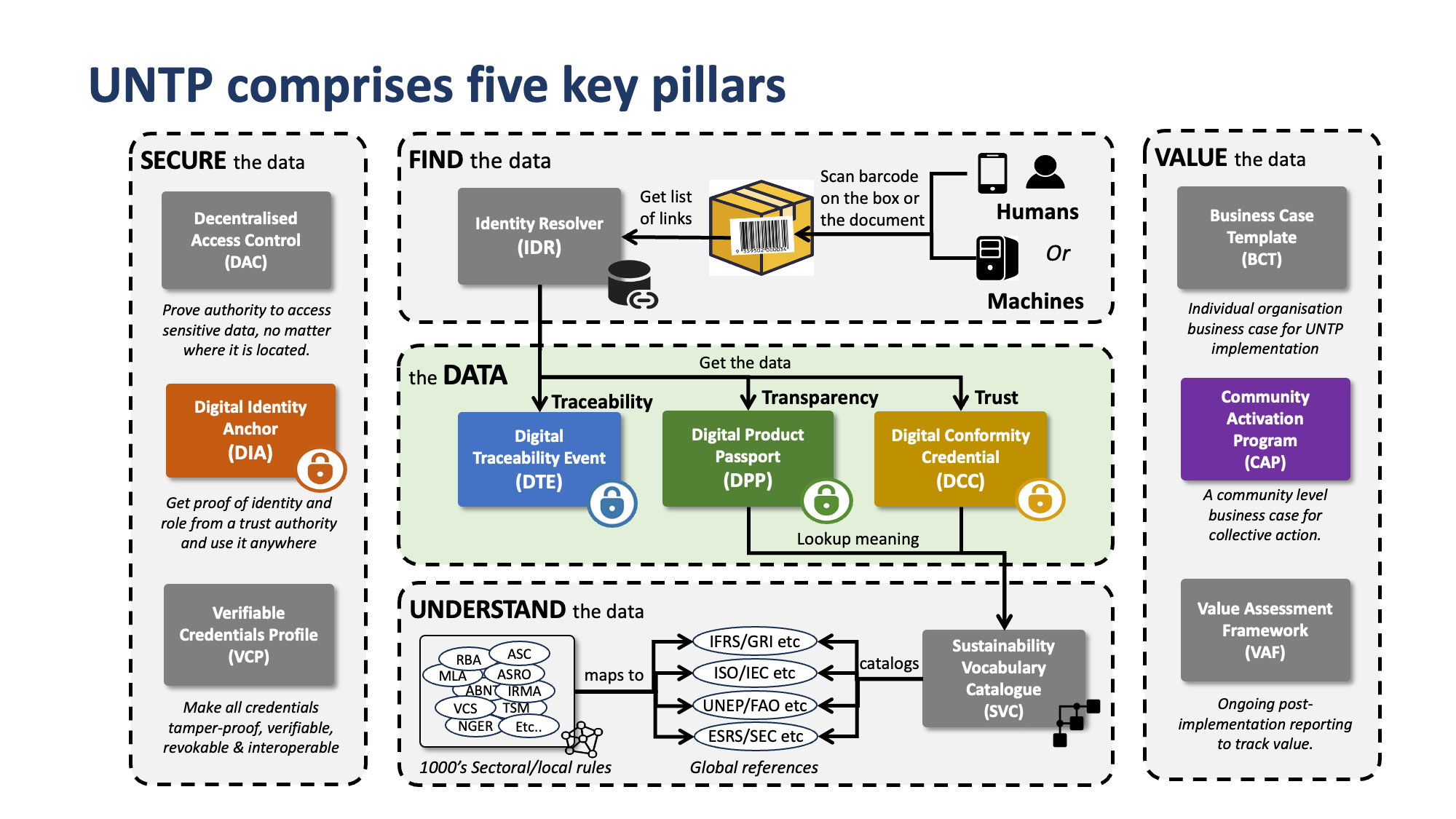

The project mission is to support global traceability and transparency at scale. To achieve that mission we must not only define the data standrds but also solve all the barriers to adoption as scale. That includes how to find the data, how to secure the data, how to understand the data, and most critically, how to realise enduring business value from the data. These are the five pillars of UNTP.

Small scale tests are possible with any of these pillars missing but scalability to full production volumes is not.

The data

The data is the heart of the UNTP. There are three different data types, each represented as digital verifiable credentials.

- The Digital Product Passport (DPP) is issued by the product manufacturer and is designed to carry basic product product data plus the conformity data (including sustainability assurance data) that is needed by the next actor in the supply chain (ie the buyer of the product). The DPP represents the conformity information as a set of "claims" that specify product performance against specified criteria. In this way, the DPP is essentially a bundle of differentiated value that a buyer can use to choose a preferred supplier. The DPP also provides a statement of material provenance (ie what materials is this product made from and where were the materials sourced). The provenance data assist with ensuring conformance to minimum local content rules or sources under sanction.

- The Digital Conformity Credential (DCC) is issued by an independent auditor or certifier and it carries one or more "assessments" of an identified product or facility against well defined criteria. When the product ID and the conformity criteria in the DCC "assessment" match those in the DPP "claim" then the DPP data value is enhanced through independent verification. The DCC must include the identity of the accreditation authority and, where relevant, links to the accreditation authority, so that verifiers can be sure that the auditor or certifier is genuine.

- The Digital Traceability Event (DTE) provides a means to trace product batch data throughout the value chain. The DTE links input products (eg bales of cotton from the primary producer) to output products (eg woven cotton fabric). Therefore the DTEs provide a means to trace product provenance through manufacturing processes to discover an entire value chain. DTEs are only available when products are managed and traceable at batch level. DTEs provide links to reach deeper into the value chain which may contain commercially sensitive data and so may only be available to authorised roles.

All three UNTP data structures are designed to be extensible to meet the needs of specific industry sectors or jurisdictions.

Finding the data

We deliberately say "finding" the data rather than "exchanging" the data because a very critical principle is that the issuer of the data usually will not know who will ultimately use it. Obviously each seller knows their immediate buyer but many other actors in a circular economy may also encounter the identified product and need to access the DPP information. It follows that a key principle of UNTP is "if you know the identifier of a product then you can get the data about the product" - even many years after the product was created.

- Identity Resolver (IDR) specifications are a concretisation of ISO/IEC 18975 that provide a standardised way to resolve an identifier (of a product, batch, item, facility or entity) to a list of links (URLs) to further information about the identified object. The format of the linkset itself is defined by RFC9264. One identifier can resolve to multiple links, each of which is annotated with a specific link type (eg UNTP DPP). The IDR works with simple identifiers (eg encoded as a traditional 1D barcode) or complex identifiers (eg encoded as a QR code). In this way a single barcode or QR code can return a rich variety of information tailored to the requestor's needs. Furthermore, the IDR can return a collection of similar link types with different date stamps or versions. One important use case for this capability to to return post-manufacture events such as consumption and eventual recycling of identified products.

Securing the data

As the value of sustainability attributes increases, so the temptation to make fake claims increases. Without confidence in the integrity of data, value is diminished. Additionally, as businesses publish more and more data about their products and upstream value chains, there is an increased risk of leakage of commercially sensitive information. Without confidence that sensitive data is accessible only to authorised parties, businesses will be less likely to participate. The UNTP security specifications address these challenges.

- Verifiable Credentials Profile (VCP). All UNTP data objects (DPP, DCC, DTE, DIA) are issued as W3C Verifiable Credentials. This ensures that the data, once issued, cannot be tampered with, that the issuer is identifiable, and that status changes like revocation are immediately visible. The VCP defines a simple subset of the larger W3C specifications so that interoperability is simpler and cheaper to achieve. The VCP also includes an human-readable rendering template extension to the W3C specification so that anyone can verify UNTP credentials even if they have no technology maturity.

- Digital Identity Anchor (DIA). The issuers and subjects of Verifiable Credentials are identified using W3C Decentralised Identifiers (DIDs) which provide a means to discover the cryptographic keys necessary to verify the credentials. However, DIDs are self-issued and do not ensure that the issuer is really who they say they are, only that the owner of the DID was certainly the issuer of the credential. The DIA is a Verifiable Credential issued by a trusted authority (eg a government agency) that links a DID to a known public identity such as VAT registration number. In this way, verifiers can be assured of the identity of issuers. The DIA also has a "scope" so that, for example a national accreditation authority can attest to the identity of a certifier but also specify the scope of the accreditation.

- Decentralised Access Control (DAC). Not all traceability and transparency data for a given product is public information. Some is accessible only to authorised roles like a customs authority or a recycling facility. Some is accessible only to the verified purchaser of a product. In centralised systems, this kind of access control is managed by granting privileged access roles to authenticated users. But in decentralised systems such as the world of DPPs, this approach is not practical. There could be thousands of different platforms that host DPPs and it would be impractical for each authorised actor to create accounts on thousands of systems. The DAC defines a simple way to encrypt sensitive data with a unique key for every unique item and a way to distribute decryption keys to authorised roles without any advance knowledge about who has which role. Even if a decryption key is lost or leaked, the scope of data access is limited to one item. The DAC also provides a mechanism for the verified purchaser of an item to update the DPP record with post-sale events like consumption, repair, or recycling.

Understanding the data

The UNTP data objects (DPP, DCC, DTE, DIA) are deliberately simple so that they are easy to understand and low cost to implement. However a lot of the structural simplicity of a DPP is achieved via the "claims" object which is a simple abstraction that can carry any sustainability or conformity metric measures against any criteria from any standard or regulation. So this simple abstraction hides a world of complexity. In a world of thousands of standards or regulations, each with dozens or hundreds of distinct criteria, how can one claim about social welfare or biodiversity be meaningfully compared to another? How can an importer know whether a product sustainability criteria from an exporting economy is equivalent to the regulated criteria in the importer's economy? As a corporate subject to sustainability disclosures under IFRS or ESRS, how can I know how to match the claims in a received product passport with the impact areas of my disclosures statement? The UNTP cannot and should not dictate which sustainability standards or regulations any given claim or assessment references. However it can provide a way to map these criteria to a harmonised vocabulary to achieve interoperability.

- The Sustainability Vocabulary Catalog (SVC) provides a framework to map sustainability knowledge across different standards, regulations and industry practices. It may not always answer the question but it provides a decentralised semantic governance model that allows mappings and corresponding value to grow over time and gaps to be fixed as they are found. The SVC is a W3C DCAT-conformant catalog of external sustainability standards and regulations. Mappings are defined using W3C SKOS and can be made either by UN working groups external standards or by external authorities to the UN catalog. This allows for a decentralised mapping effort that is far more scalable than depending on a small centralised team.

As uptake of UNTP grows, maintenance of the SVC is one of the key activities that grows with uptake and adds continuously increasing value to the global sustainability effort.

Valuing the data

Without sufficient commercial incentive, businesses will not act. In some cases the commercial incentive is regulatory compliance. But few economies (The European Union is a notable exception) have current or emerging regulations that demand digital product passports for products sold or manufactured in their economy. However, there is much wider regulatory enforcement of annual corporate sustainability disclosures. But without sustainability data from supply chains at product level, there is no easy way for corporates to accurately meet their annual disclosure obligations. Worse, without product level data from suppliers, there is no way at all for corporates to select suppliers in such a way that they can demonstrate year-on-year improvements to sustainability performance. On top of the disclosure obligation, most corporates are very concerned about reputational risk associates with un-sustainable behaviour from their upstream suppliers. Furthermore, the financial sector is increasingly able and willing to provide improved financial terms for trade finance or investment capital to businesses with strong sustainability credentials. All these incentives drive behaviour and value but there is still some effort needed for each implementer to make a positive business case for change. UNTP offers some tools to determine the value that can inform a positive case for change.

- Business Case Template (BCT). A simple template for each role (buyer, supplier, certifier, software vendor, regulator, etc) to make a business case for the investment needed to implement UNTP. Continuously updated and improved with lessons from early implementations, the BCT provides a quick way for sustainability staff to support for their budget requests.

- Community Activation Program (CAP). Supply chain actors are often reluctant to proceed with a specific initiative like UNTP unless they have some confidence that others in their industry are doing the same. There are not only obvious interoperability benefits from industry-wide adoption but also cost benefits. For example, it is often the case that a small number of commercial software platforms are commonly used by larger numbers of businesses in a given industry and jurisdiction. So a software vendor that implements UNTP once will benefit all its customers. Additionally there are often a few standards and a few certifiers that are common to an industry and country. Likewise, there is very often one or more existing member associations that represent most of the actors in a given industry and country. Finally, when a large community is willing to act together, there will often be financial incentives from governments and/or development banks that can assist with initial funding. In short, there are many reasons to approach UNTP implementation at a community level. The CAP is a business template for a community level adoption of UNTP including a tool for financial cost/benefit modelling at community level.

- Value Assessment Framework (VAF). Once a community or individual implements UNTP and transparency data starts to flow at scale, it will become important to continuously assess the actual value that is realised. Dashboards and scorecards that measure key performance indicators will energise ongoing action and provide valuable feedback at both community and UN level. Therefore the UNTP defines a minimal set of KPIs that each implementer can easily measure and report to their community - and which communities can report to the UN.

Project Deliverables

White paper covering guidance material for developing Data Governance framework and guidance to facilitate secure exchange of domestic and cross border data especially in the context of trade

FILE SHARING WIZARD

Upload you project files here. The wizard will organize them according to their filenames. For example, a documents such as - minutes_of_15122015.docx - will be shown under the Meeting Minutes

show me all the attachments in this deliverable

| OUTPUT TYPE | FILES |

|---|---|

DRAFTS | |

MEETING MINUTES | |

MEETING AGENDA | |

BACKGROUND DOCUMENTS | |

COMMENT LOGS | |

PRESENTATIONS |